Ask a Neuroscientist: What is the origin of psychopathology?

/“A question: Several schools of classical psychoanalysis have contended that emotional and behavioral problems arise, for the most part, out of inner conflict in the psyche. Yet neuroscience apparently has little to say about the psyche or about inner conflict. Science has not been able to say whether inner conflict—the clash of competing impulses, irrational wishes, and primitive drives—even exists or what influence such inner chaos might have on us.

Why is science silent on this question?”

The essential question here is: What is the origin of psychopathology? That question does receive intense attention from the sciences. There are many modern approaches to answering it, and psychoanalytic theory provided one of the first. So what do neuroscientists and psychologists today think of those early efforts? Why isn’t there a paper out there today entitled “The neural basis of Freudian repression of primitive drives”?

Freud founded psychoanalysis with the theory that neurosis—a grab bag of anxiety, mood and personality disorders—arose from friction between the components of the mind. He argued that anxiety welled up from the frustration of the basic, instinctual drives of the id by the superego, playing the role of chaperone at the school dance. The id would then become a little pressure cooker, forcing the patient to find some creative manner—a defense mechanism—to relieve the intrapsychic tension.

Freud spent the first two decades of his career as a highly productive neurologist. His interest in psychology grew from his attempts to cure and understand patients with hysterical paralyses—paralysis with no visible physical cause. (Oliver Sacks wrote a fabulous essay on Freud’s transition from neurology to psychology in the book Freud and the Neurosciences, if you’re interested in learning more.)

In 1895, in a burst of theoretical activity, he scribbled down a grandiose manuscript called Project for a Scientific Psychology. In the Project, he tried to link fundamental psychological phenomena—memory, sensation, consciousness—with his cutting-edge knowledge of the brain.

And there’s the issue, right there. Freud’s cutting-edge knowledge of the brain—and that of his many successors in the first half of the 20th century—did not amount to much.

Consider the raging neuroscientific debate in the late 1800s, while Freud was a practicing neurologist. They knew the brain contained neurons and a tangle of filamentous cellular appendages (axons and dendrites), but they couldn’t see well enough with current microscopes and imaging techniques to tell whether they were all one continuous cell connected by these filaments, or a billion different cells with ultra-tiny boundaries. Golgi and Ramon y Cajal would share the Nobel prize in 1906 for settling that one: The brain was made up of many separate neurons with tiny boundaries, later termed synapses.

One of Santiago Ramon y Cajal's famously precise drawings of neurons. From "Structure of the Mammalian Retina" Madrid, 1900.

Contrast the clear limitations of their knowledge of the brain with Freud’s optimism about his neuroscientific theory of the mind:

“One evening last week when I was hard at work… the barriers were suddenly lifted, the veil drawn aside, and I had a clear vision from the details of the neuroses to the conditions that make consciousness possible. Everything seemed to connect up, the whole worked well together, and one had the impression that the Thing was now really a machine and would soon go by itself… naturally I don’t know how to contain myself for pleasure.””

Well, everything can’t possibly have connected up then, because I can tell you for sure it still hasn’t.

I read some of the Project, though, and it was a wild experience. It’s really hard to understand given the fact that Freud pretty much had no idea what he was talking about, and yet it is incredibly insightful given the limitations of his scientific knowledge. Scientists wouldn’t have a name for synapses for ten years, for example, but that didn’t stop Freud—who called them ‘contact-barriers’—from correctly postulating a role for synaptic plasticity in memory.

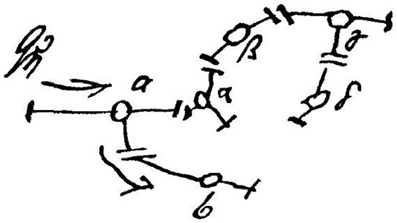

Freud's sketch of his proposed neuronal basis of repression, from Project for a Scientific Psychology. He proposed that repression requires inhibition of neuronal activity, but no one had yet discovered that neurons communicate with neurotransmitters, including the inhibitory neurotransmitter, GABA. In this sketch, he tries to show how inhibition could be achieved by diverting neuronal activity away from its intended destination, almost like water or electrical current.

Despite Freud’s initial fervor, Project for a Scientific Psychology was never published. Perhaps frustrated, he abandoned all attempts to link mental phenomena with their biological underpinnings and turned to pure psychology. Psychoanalysis would kick off with Studies on Hysteria, published in that same year.

The desire to connect our understanding of the mind and the brain simmered quietly over the years, however. In the second half of the 20th century, the field of neuroscience really started to take off, and people started chipping away seriously at the problem. Bill Newsome’s ongoing work on perceptual decision-making that Nick Weiler reviewed in a recent post is a fantastic example.

Both neuroscience and psychology have grown and changed radically since the heyday of classical psychoanalysis, though, so the influence of psychoanalytic theory on contemporary thought may not be obvious. But it’s there!*

One reason you don’t see the same jargon and assumptions being bandied about is that our methodology has changed so much. Case studies, so important in psychoanalysis, aren’t used today unless people are studying rare human illnesses. And scientists try to achieve objectivity by employing external behavioral indicators of mental processes, control groups, large sample sizes, and rigorous statistics. These methods may sound woefully impersonal compared with the colorful drama of psychoanalytic case studies, but that’s the cost of removing the experimenter’s personal biases to the extent possible.

Nonetheless, many of the premises of psychoanalytic theory have survived the test of time. The Implicit Association Test, for example, is an experimental paradigm that can be used to identify conflicts between conscious and unconscious attitudes. And work by Stanford psychologist James Gross found that people who rely heavily on “emotional suppression” to regulate their emotions (a construct that sounds reasonably similar, but not identical, to Freud’s “repression” to me) are more likely to develop anxiety or depression.

Another approach you may find interesting is Joshua Greene’s work on the role of the frontal lobe in mediating emotional and intellectual reasoning in moral conflicts. He discusses the effect this chaos has on us in his book Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason and the Gap between Us and Them.

Freud was an incredible intuitive, and his capacity for generating ideas far outstripped the material available to feed them. It’s a sad truth that rigorously establishing a fact is a laborious and at times deeply boring process. It’s much more fun to fly along as fast as the mind can work—if you don’t mind being wrong as often as not.

* A great discussion of the lasting contributions of psychoanalysis to modern psychology and a critique of its limitations can be found in the textbook The Personality Puzzle by David Funder.